Table of Contents

This post treats reward functions as “specifying goals”, in some sense. As I explained in Reward Is Not The Optimization Target, this is a misconception that can seriously damage your ability to understand how AI works. Rather than “incentivizing” behavior, reward signals are (in many cases) akin to a per-datapoint learning rate. Reward chisels circuits into the AI. That’s it!

NoteHere are the slides for a talk I just gave at chai’s 2021 workshop.

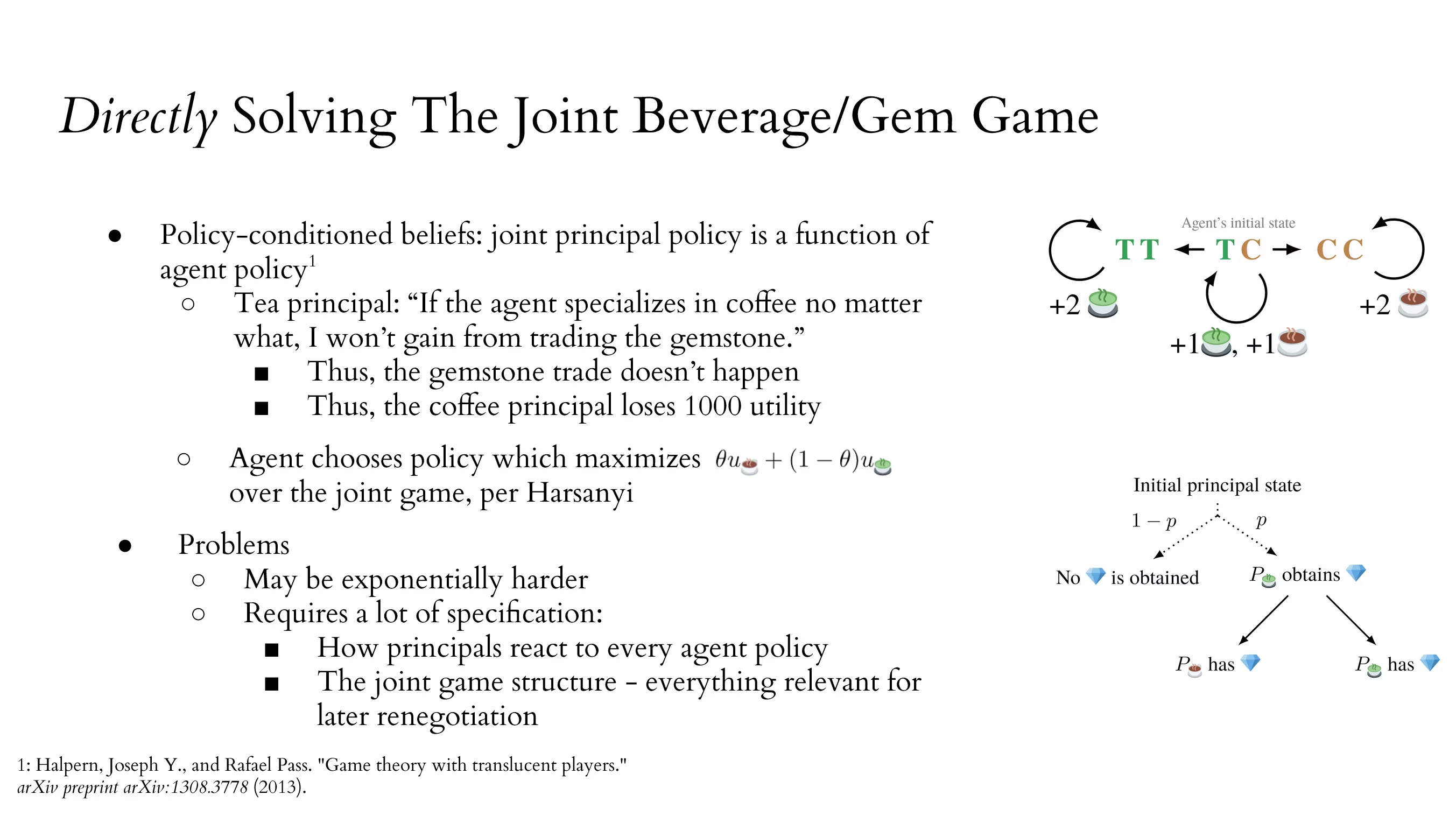

The first part of my talk summarized my existing results on avoiding negative side effects by making the agent “act conservatively.” The second part shows how this helps facilitate iterated negotiation and increase gains from trade in the multi-stakeholder setting.

Summary of results: aup does well.

I expect aup to further scale to high-dimensional embodied tasks. For example, avoiding making a mess on e.g. the factory floor. That said, I expect that physically distant side effects will be harder for aup to detect. In those situations, it’s less likely that distant effects show up in the agent’s value functions for its auxiliary goals in the penalty terms.

I think of aup as addressing the single-principal (AI designer) / single-agent (AI agent) case. What about the multi / single case?

In this setting, negotiated agent policies usually destroy option value.

![Why negotiated agent policies destroy option value: ... - Principals share beliefs and a discount rate γ ∈ (0, 1). ... - Harsanyi’s utilitarian theorem implies Pareto-optimal agent policies optimize utility function θu☕️ + (1 – θ)u🍵 for some θ ∈ [0, 1]. ... - Unless θ = 1/2, the agent destroys option value.](https://assets.turntrout.com/static/images/posts/option-value-multiple-stakeholders-conservative-agency.avif)

This might be OK if the interaction is one-off: the agent’s production possibilities frontier is fairly limited, and it usually specializes in one beverage or the other.

Interactions are rarely one-off: there are often opportunities for later trades and renegotiations as the principals gain resources or change their minds about what they want.

Concretely, imagine the principals are playing a game of their own.

We can motivate the mp-aup objective with an analogous situation. Imagine the agent starts off with uncertainty about what objective it should optimize, and the agent reduces its uncertainty over time. This uncertainty is modeled using the ‘assistance game’ framework, of which Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning is one example. (The assistance game paper has yet to be publicly released, but I think it’s quite good!)

Assistance games are a certain kind of partially observable Markov decision process (pomdp), and they’re solved by policies which maximize the agent’s expected true reward. So once the agent is certain of the true objective, it should just optimize that. But what about before then?

![An assistance game is solved by optimizing a reward function, R(s), at a discount rate γ' ≝ (1-p)γ. The function equals a term to "Optimize negotiated mixture of utilities," which is θu_coffee(s) + (1-θ)u_matcha(s), plus a term to "Preserve attainable utility for future deals," which is [p/(1-p)] * [θV_u_coffee(s) + (1-θ)V_u_matcha(s)].](https://assets.turntrout.com/static/images/posts/solve-mp-aup.avif)

Suggestive, but the assumptions don’t perfectly line up with our use case (reward uncertainty isn’t obviously equivalent to optimizing a mixture utility function per Harsanyi). I’m interested in more directly axiomatically motivating mp-aup as (approximately) solving a certain class of joint principal / agent games under certain renegotiation assumptions, or (in the negative case) understanding how it falls short.

Here are some problems that mp-aup doesn’t address:

- Multi-principal / multi-agent: even if agent A can make tea, that doesn’t mean agent A will let agent B make tea.

- Specifying individual principal objectives

- Ensuring that agent remains corrigible to principals—if mp-aup agents remain able to act in the interest of each principal, that means nothing if we can no longer correct the agent so that it actually pursues those interests.

Furthermore, it seems plausible to me that mp-aup helps pretty well in the multiple-principal / single-agent case, without much more work than normal aup requires. However, I think there’s a good chance I haven’t thought of some crucial considerations which make it fail or which make it less good. In particular, I haven’t thought much about the principal case.

I’d be excited to see more work on this, but I don’t currently plan to do it myself. I’ve only thought about this idea for <20 hours over the last few weeks, so there are probably many low-hanging fruits and important questions to ask. Aup and mp-aup seem to tackle similar problems, in that they both (aim to) incentivize the agent to preserve its ability to change course and pursue a range of different tasks.

ThanksThanks to Andrew Critch for prompting me to flesh out this idea.

Find out when I post more content: newsletter & rss

alex@turntrout.com (pgp)